How Do We Know It's A Dye? The Historic Record.

In the Natural Dye Education community, members regularly help each other determine if a particular plant, fungus, lichen, insect, etc. has dye potential. But sometimes the discussion goes something like this.

How Do We Know Anything?

These discussions always make me think about the philosophy courses I took, during my undergraduate days, on the nature of knowing: what are the different ways we can know something? And what does it say if we think there is something we can learn - by trying ourselves - that has not been learned already by our highly skilled ancestors, or by highly trained scientific experts?

Over the next several blog posts, I’m going to provide some helpful resources to assist in accessing some of the knowledge of hypothetical Member 2 and Member 3, and to know when Member 4 might be on to something. I have also been prompted to do this as a result of changes in the way that Facebook is structuring groups. When I started my group, I spent a huge amount of time compiling high quality resources and shared them through subject-specific group Files. However, Facebook is fazing Files out, and I recently lost a File that represented hundreds of hours of labour, when I simply tried to edit it. So, in the interests of a more secure platform for sharing this information, less vulnerable to Facebook’s ever-changing whims, I am migrating the information to my web site, instead.

In the first in this blog series, I am focusing on the historic dye record as one important Way Of Knowing, including:

ancestral knowledge; and

written dye manuals.

The Historic Record

Ancestral Knowledge

Maybe you are lucky enough to have had time with an elder who has passed on her natural dye wisdom to you. Most of us have not. For many, our connection to ancestors who would have been deeply experienced with the once common skills of effective natural dyeing has been severed by time, migrations, and various cultural and historic upheavals.

Great Aunt Mary

migrated from Ireland to Canada in the mid-1800s, with my one year old Mom on the Alberta family farm, 1925

My own ancestry is predominantly Irish. My ancestors came to Canada in the mid-1800s, fleeing The Great Hunger and merciless English colonial overlords. Because dyeing was once practiced by virtually every household, I assume that my ancestors possessed dye knowledge and skills. But there is no surviving record of what they may or may not have known. Even at the national level in Ireland, historic upheavals and the loss of seven centuries of historic records to fire in 1922 during the Irish Civil War make it challenging to access the ancestral dye knowledge of that land. There are tantalizing tidbits in a very few resources, but that is all.

So when we do find ethnobotanical knowledge of various people meticulously documented and published for posterity, and even more so when it is freely available online, it really is treasure. Even for those of us not descended from the peoples whose wisdom is documented in the below, once we understand something of shared botany (for example, many plant species native to eastern Canada, where I now live, are also native to Ireland), we can suppose that there may once have been knowledge of the usefulness of the same plant species for dyeing in geographically distant lands.

This is a reasonable assumption, as with the written and material record that we do have, we see time and again that peoples in far flung regions developed very comparable dye knowledge of even the most complex of methods - such as the extraction and use of indigo - long before they ever had contact with one another.

If you are lucky, an enterprising member of your local fibre guild may have researched and written a pamphlet or book on natural dye history for your region. It’s always worth checking with guilds.

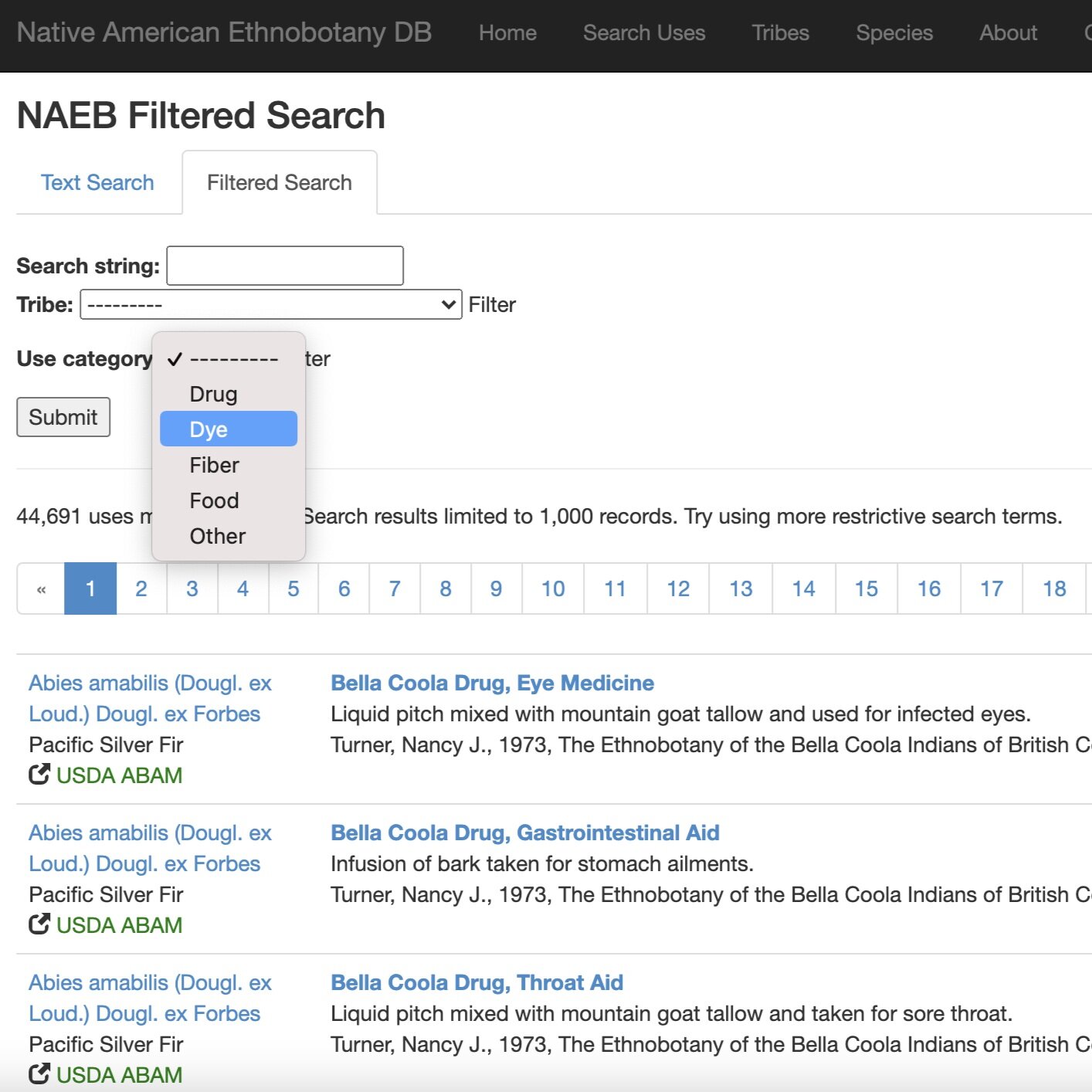

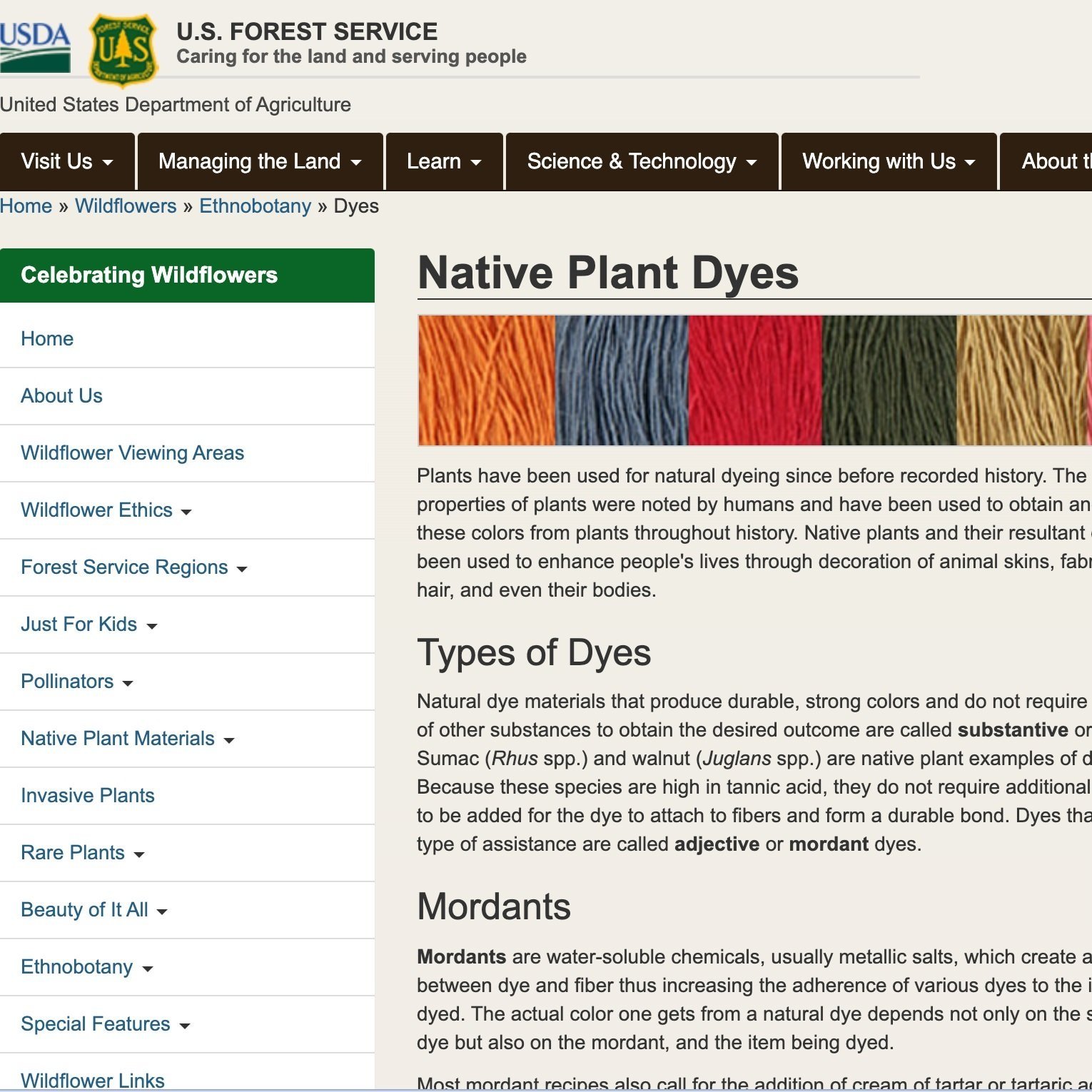

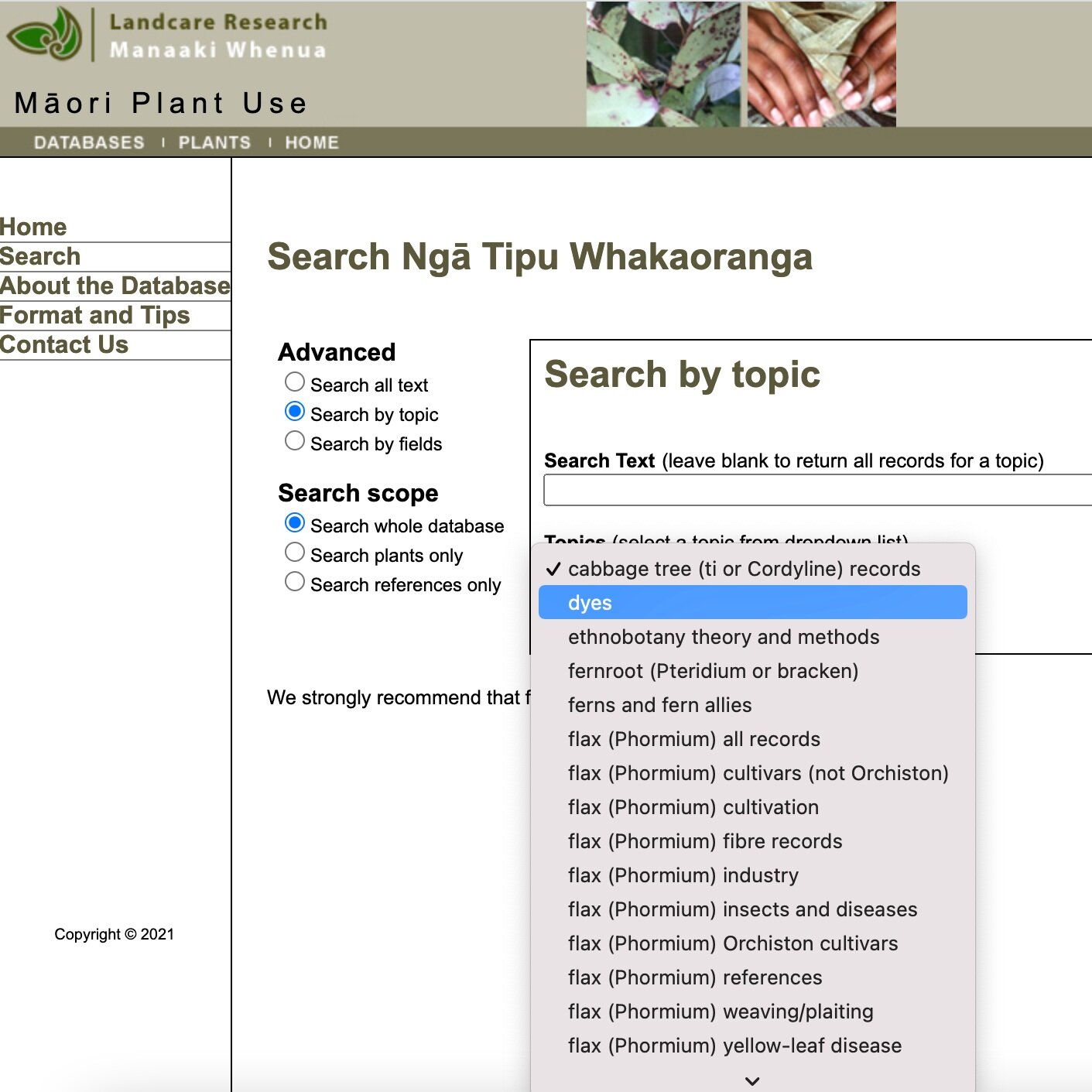

While the below are the only online comprehensive ethnobotany databases that include dye species that I’ve found so far, many universities have programs in ethnobotany, so if your part of the world is not covered by one of the below, try contacting someone in an ethnobotany department to ask if they have a list of plants from your region that were traditionally used for dye.

If you are aware of other online ethnobotany databases useful to natural dyers, please do let me know!

Clicking on any of the below will take you to the database.

The Historic Record

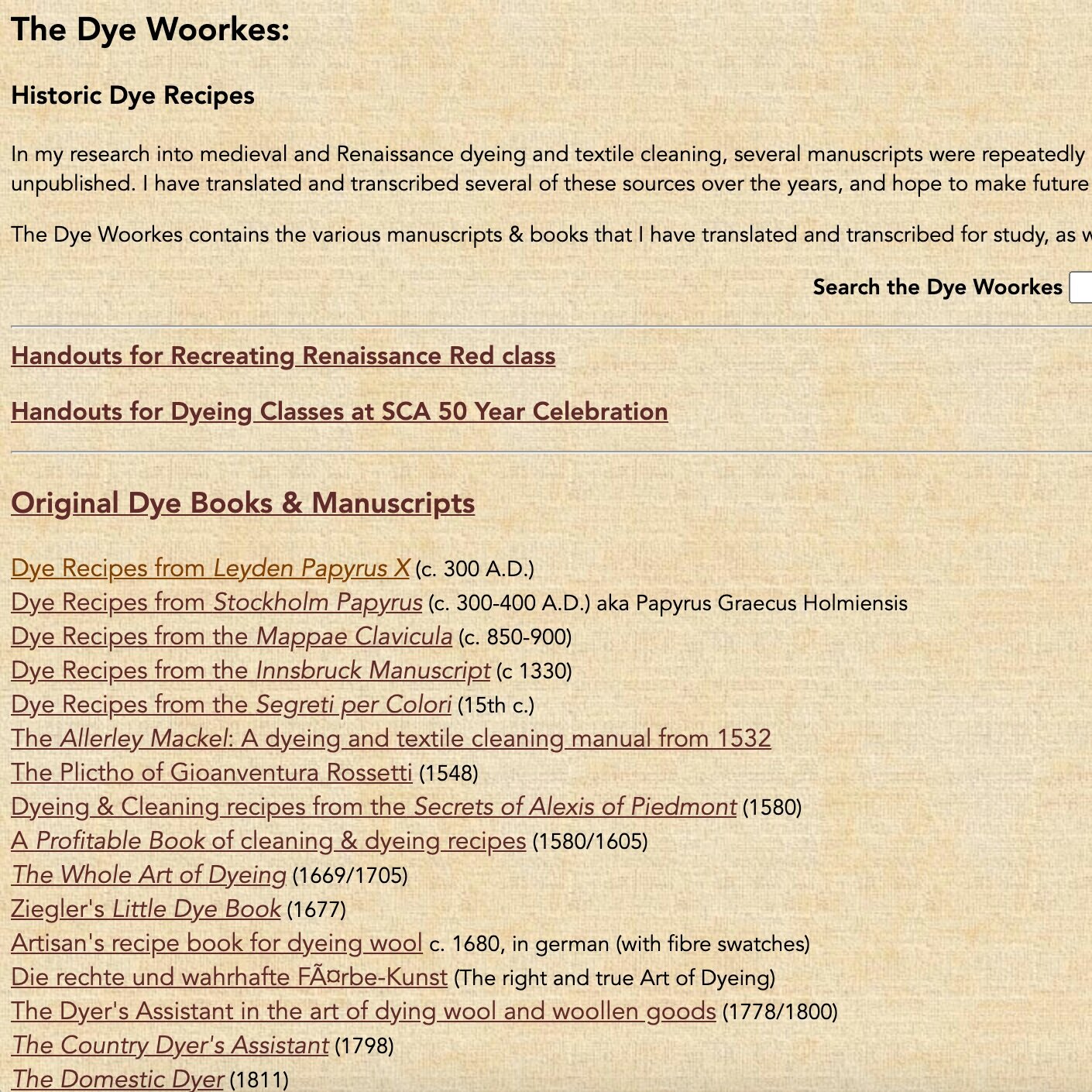

Written Dye Manuals

There are undoubtedly many other excellent written dye manuals, including many historic works in languages I do not speak, but I have included the below because:

they are written or have been translated into English, which is the most widely spoken language in the world (not necessarily as a first language); and

they are available for free online.

Whenever I think about the written dye record, I always think about all of the great libraries of the world that have been burned to the ground - often intentionally, sometimes accidentally - and the painstaking accumulation of centuries of knowledge that was lost in those disasters. For example, what cultural practices, including dye knowledge, was wiped from the Earth when Spanish invaders destroyed all but four of the thousands of ancient Maya Codices? Of course, this also applies to people who may not have had a written language, but whose libraries - housed in their minds and in community practices - were destroyed when the people were wiped out, as often happened during violent campaigns of colonization.

So my own language limitations (English, French, and some Spanish - so all European), plus the destructive legacy of European colonialism, make this list Euro-centric. If anyone is compiling comparable resources in other languages, and from other cultures, I would be happy to include a link.

In chronological order, from 5,500 BC to the early 20th century…

Honourable Mention:

While it’s not an online ethnobotany database, and not an online historic dye manual, I would like to give a shout out to the Asian Textile Studies web site. I have not, to date, found any online ethnobotany databases or online historic dye manuals for the many rich natural dye traditions of Asia, but the couple behind this web site have created an invaluable catalogue of regional natural dyes and textile traditions.

So If There’s No Record…

A few years ago, the US Department of the Interior published a study which showed that the average American child can identify 1,000 corporate logos, but can’t identify 10 plants and animals native to his or her hometown. I’m sure this is true of people in most parts of the world these days. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, and even well into the 20th century in many places, the reverse was true. The average person had an encyclopedic knowledge of the natural world.

Much of humanity’s knowledge of sources of reliable natural dyes was developed over millennia by people deeply connected to Nature. Until the late 20th century, most people on Earth lived as hunter-gatherers and as agrarians, producing their own food, clothing, candles, soap, medicines, etc. Particularly prior to the Industrial Revolution (18th century onwards), most people knew how to make almost anything they needed from the natural materials in their immediate surroundings. So, for thousands of years, humans lived in very close relation to Nature, understanding the properties of, and multiple beneficial uses to which they could put, many different natural materials.

I once observed a discussion online where someone was proposing that Spinach could be a good and easy source of green dye for fibres. Others were pointing out that pretty much universally, people have historically created green dye through the use of an indigo-bearing species and the use of a yellow dye species - a lengthy process that combines two primary colours to create secondary green. The Spinach proponent suggested that perhaps no-one in the past had ever figured out that Spinach could be used as a green dye.

But my feeling about such a line of enquiry is that it starts from the wrong premise. It comes from not thinking through the basic facts of human history, of how people lived immersed in a day to day dependence on Nature. Instead, I would suggest that much more respectful questions to ask would be…

“Does it seem reasonable that people in the past who lived with such intimate knowledge of Nature would not have used spinach as a dye source if it were actually a reliable one?”

“does it seem reasonable, given how physically hard their lives were, with none of our modern labour-saving technology, that they would have so repeatedly used the much more complex process of indigo and a yellow dye, if they could have used a much less time and labour intensive method of just grabbing a handful of spinach from their vegetable garden?”

So, in our journey as natural dyers, when we make an effort to find and read as much of the available historic dye record as we can, we start to notice certain things.

The historic record is vast.

Often the same plants (or species from other Kingdoms) appear time and again, down through the years, in different ethnobotanical sources and written dye manuals. This doesn’t necessarily mean they are the only species that contain useful dyes, but it does mean that over the generations of those who came before, there was a distillation of knowledge of dye sources that met certain criteria - good colour, good colour fastness, and a good return on investment of the time and labour involved in foraging or growing it.

In the historic dye record, none of the plants are anywhere to be found that are so wildly popular these days with social media users more focused on selling than telling it like it truly is - things like berries, red cabbage, black beans, hollyhocks and other red/pink/purple/blue flowers, or avocados. Would the historic record not be full of the use of these easily available plants (in their respective geographic regions) if they were actually reliable fibre dyes?

Dye manuals were often written by and/or for professional dyers whose reputations and livelihoods depended on producing the most beautiful, and the most long-lasting colour. These dyers were most likely to use a smaller number of commercially grown and traded dye species, from which they could craft a rainbow of colours with good fastness properties.

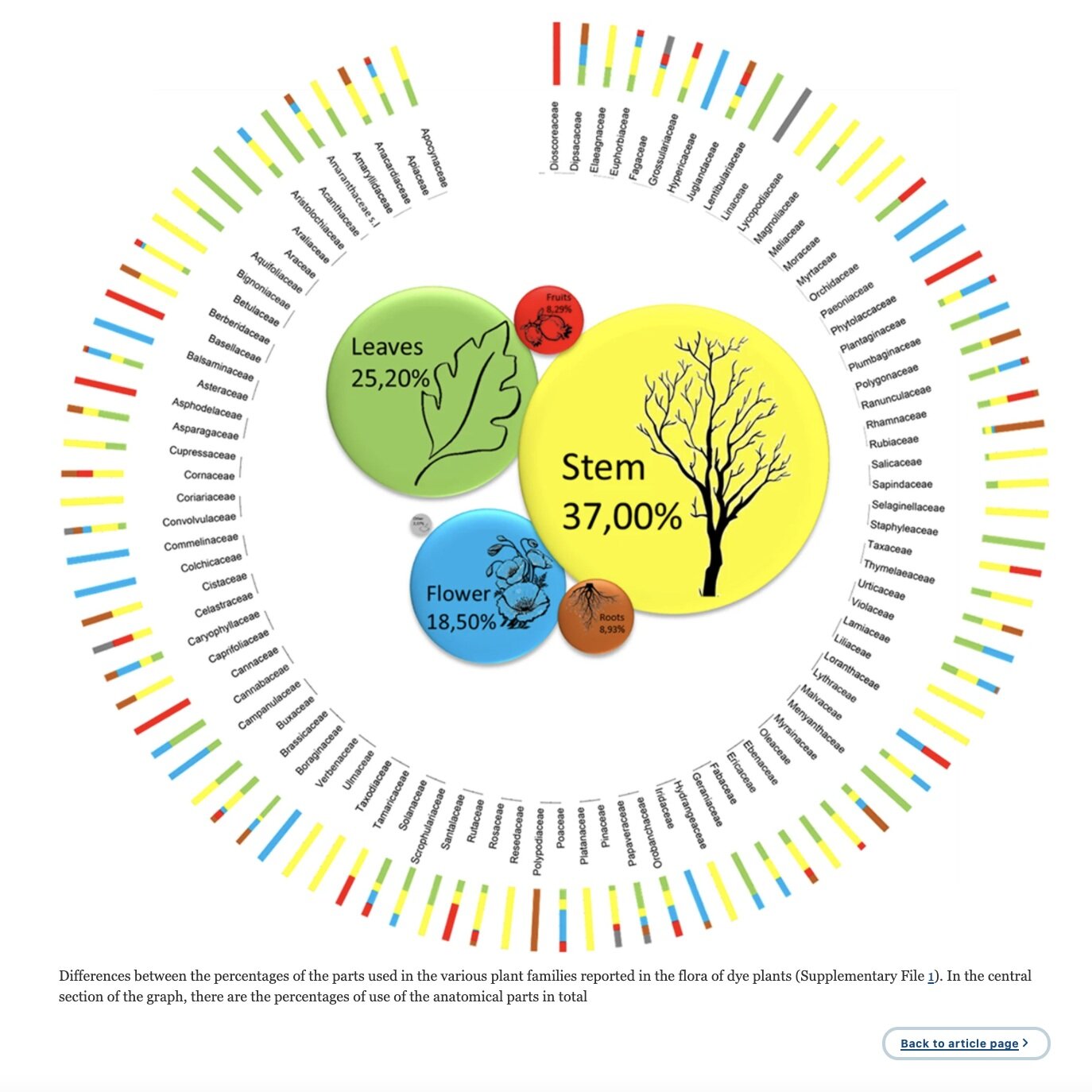

Ethnobotanical records, on the other hand, preserve more of the non-commercial dye wisdom - the much larger number of species that different people could find growing in their immediate vicinity, and that provided them with different dye sources across the seasons.

“There is nothing new in the universe except the history you do not know.”

So, the first (but not the only) question to ask ourselves when wondering if something is a dye species is:

“Is there a record of it in the historic dye literature?”

None of the above should be interpreted as implying that there isn’t any new dye knowledge to be discovered. I look forward to addressing that in subsequent posts in this series, and in my very next blog post, I will delve into the natural dye scientific record as another Way Of Knowing.

If you found the above helpful, please like or comment below (so I know someone is reading this! 🙂).

Cheers, Mel Sweetnam

Mamie’s Schoolhouse, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada (July 2021)